In the lead up to the second world war, Jewish families across Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and other European countries packed hurriedly, hoping to find safety beyond their borders. They often sold what they could and surrendered the rest to the German state; their homes and savings exchanged for the right to leave.

But as doors closed one after another, escape became a privilege few could claim. In the summer of 1938, when representatives from thirty-two nations met at Évian in France, they spoke in tones of sympathy but acted with restraint. The New York Times reported that delegates expressed “great sympathy” but “made it clear that no country would be able to receive any considerable number of refugees.”[1] Only the Dominican Republic offered to take more. For the remaining individuals and families, the world’s silence deepened the despair.

In Britain, the government feared the burden of new arrivals in a time of high unemployment, but refugee aid organisations such as the Jewish Refugee Committee and the Movement for the Care of Children in Germany (Refugee Children’s Movement), continually advocated for their cause as they had throughout the 1930s, particularly regarding the plight of children in Nazi-occupied territories. Ordinary citizens acting privately or as part of voluntary aid, religious and community groups stepped up to provide care, housing and employment, raise funds, and sponsor those trying to flee persecution. British Jews and Quakers were particularly pro-active.

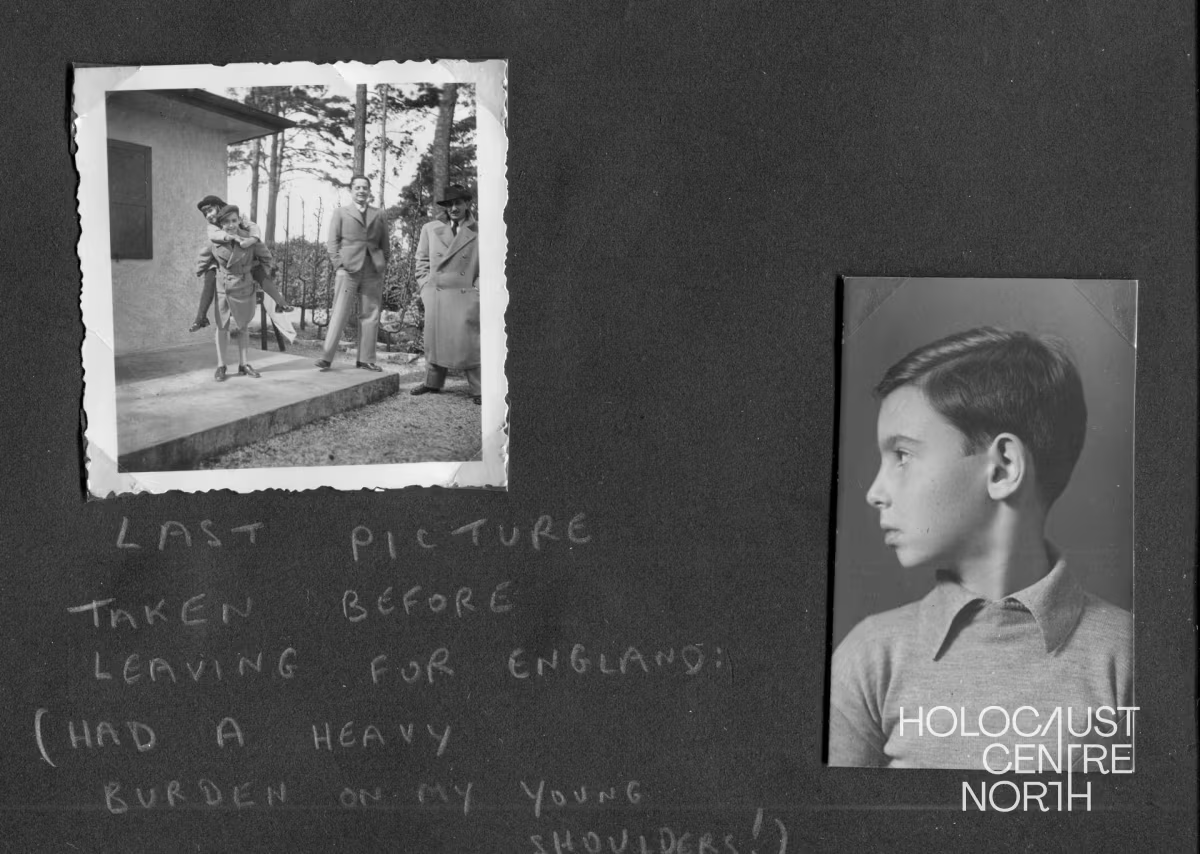

Striking page from David Berglas’ family photo album, capturing their last days at home in Germany before emigration. With David’s later poignant reflection that he “had a heavy burden on my young shoulders!”

Courtesy of David Berglas

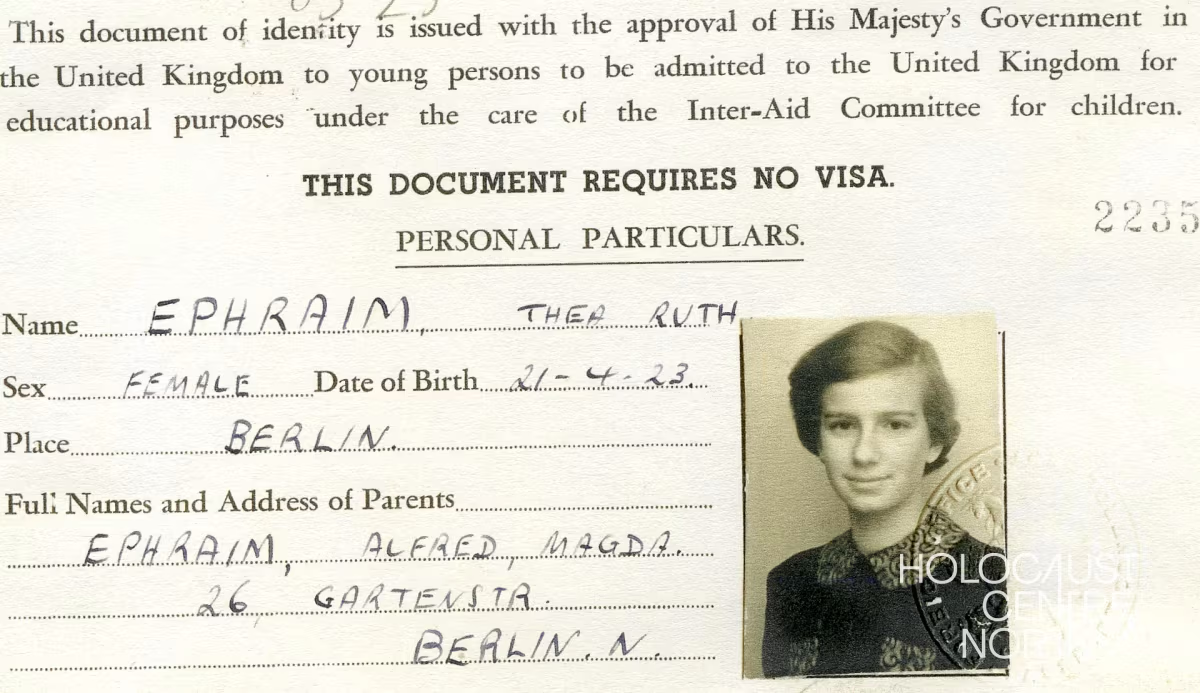

Identification document for Thea Ephraim, showing her approval to enter the UK under the care of the Inter-Aid Committee for children.

Courtesy of the Skyte family

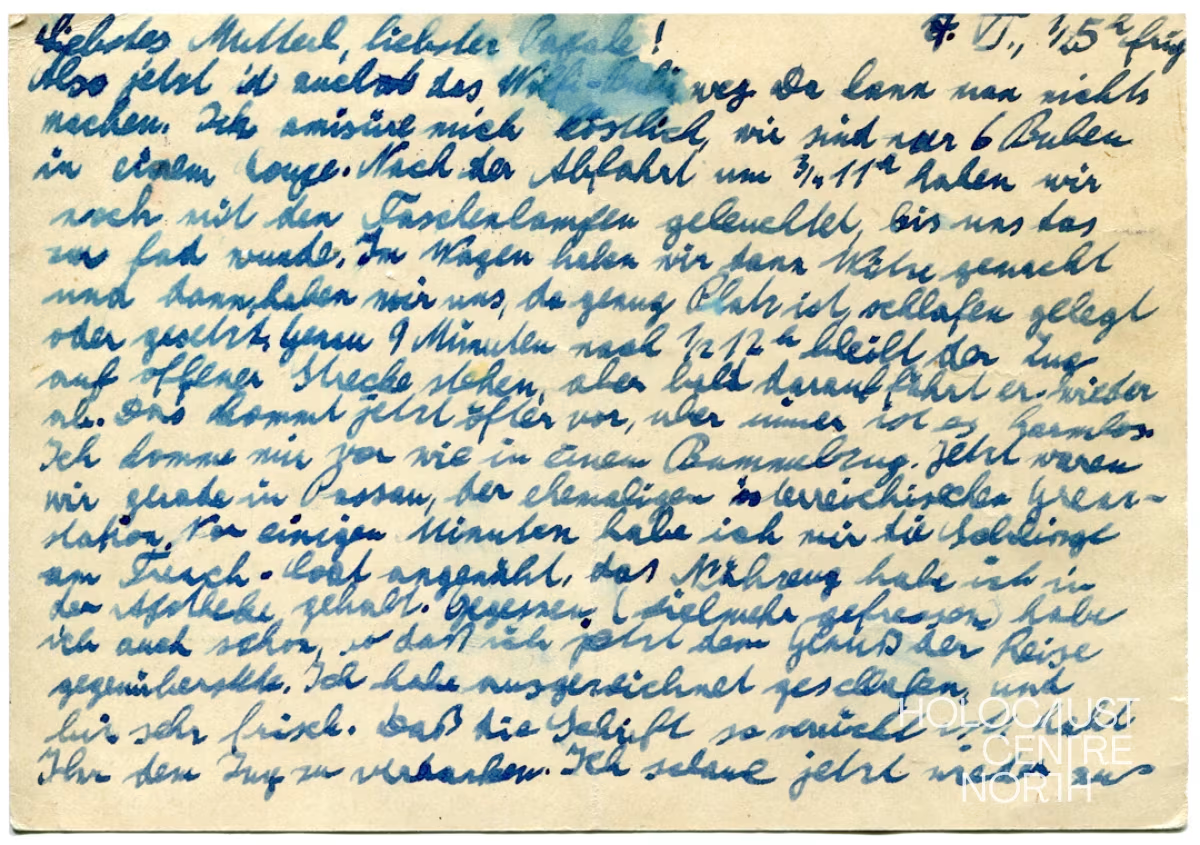

Twelve-year-old Marc Schatzberger’s intentionally upbeat postcard to his parents, written en route to England whilst on the Kindertransport.

Courtesy of the Schatzberger family

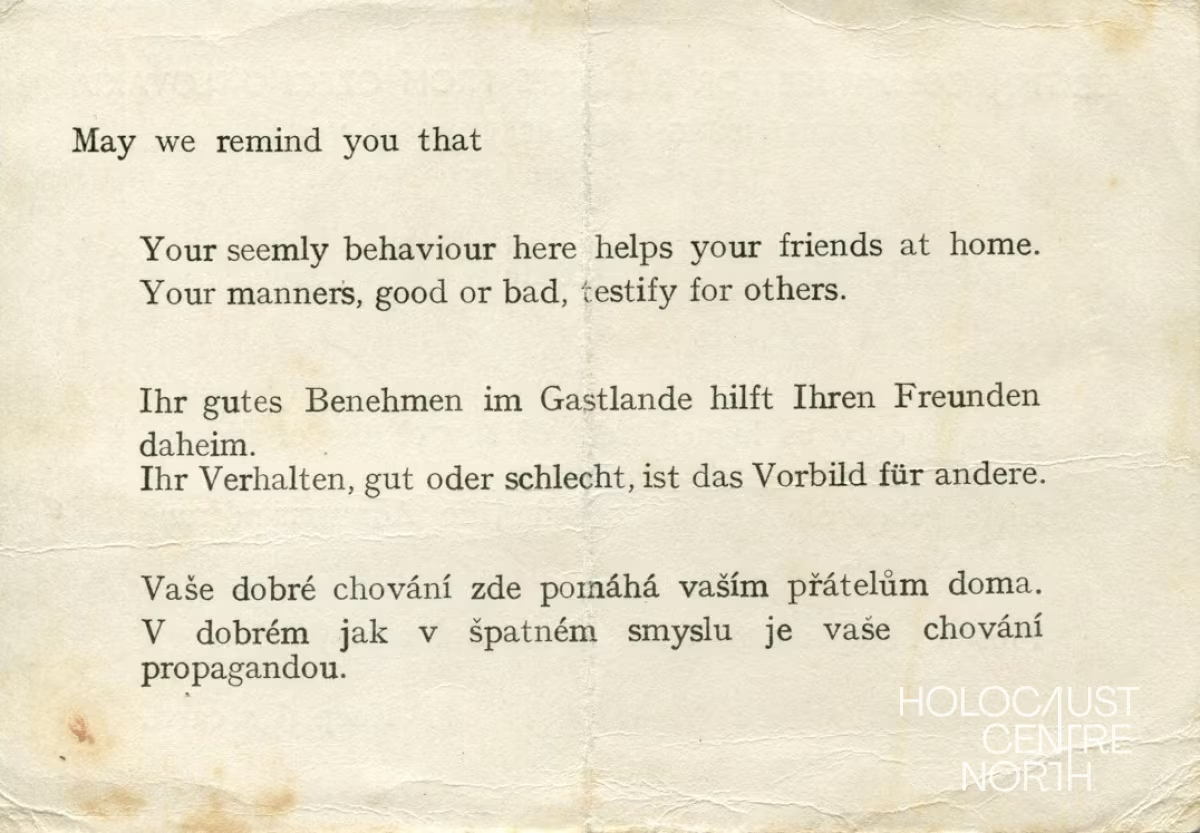

Reverse of Trude Silman’s identification card issued by the British Committee for Refugees from Czecho-Slovakia, reminding her that: Your seemly behaviour here helps your friends at home. Your manners, good or bad, testify for others.

Courtesy of Trude Silman & family

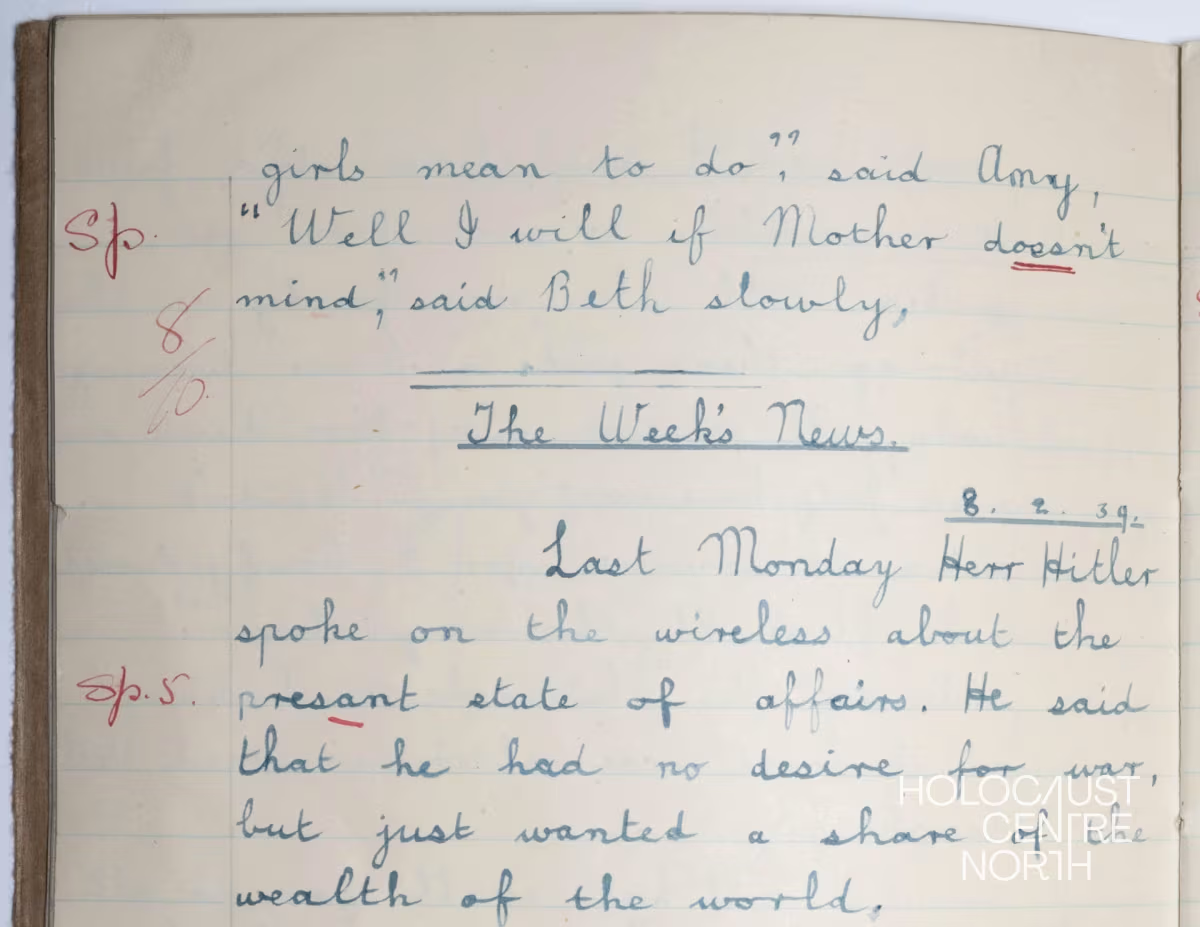

School pupil Yetta Rosenberg’s account of the week’s news in February 1939, in which she notes that “Herr Hitler” said that he had “no desire for war but just wanted a share of the wealth of the world.”

Courtesy of Emma Falk

The violence of the 1938 November Pogrom (also known as ‘Kristallnacht’ or the ‘Night of Broken Glass’) was a turning point. Overnight in Nazi-occupied Europe synagogues were set alight, shops were smashed, and thousands of Jewish men were arrested. Public opinion in Britain was mobilised and within weeks the British government agreed to admit children under the age of seventeen. This became known as the Kindertransport scheme, an extraordinary effort which brought nearly 10,000 Jewish children to the UK between December 1938-September 1939 and has become one of the most well-known child rescue initiatives.

Private citizens or organisations had to guarantee payment for each child's care, education, and eventual emigration from Britain. In return, the British government agreed to allow unaccompanied refugee children to enter the country on temporary travel visas. Local communities responded rapidly, organising hostels, such as the Bradford Jewish Refugee Hostel for boys, whilst increasing numbers of foster families opened their homes. It was understood that these young refugees would just be in the UK for “for the duration of the emergency” and when the “crisis was over” they would return to their families.[2] Few imagined how long this would be, or how far from home it would take them.

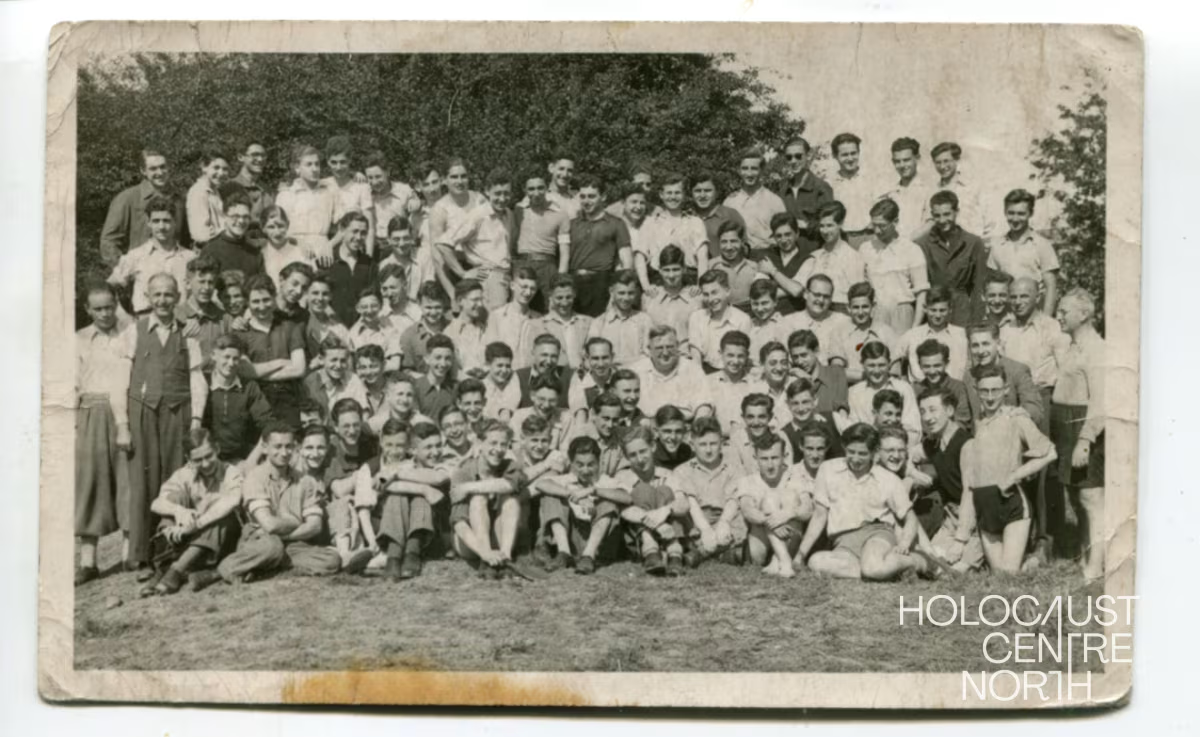

Teacher Julius Reiss (middle, far left) pictured with staff and pupils from the Berlin ORT school for Jewish boys, which was relocated to Leeds during the war. Here they are at the Kitchener Camp in September 1939, where they stayed until the Leeds site was ready.

Courtesy of Norma Fineberg & family

Members of the Young Austria youth club play tug of war in the English countryside, 1944.

Courtesy of the Schatzberger family

Eric Schrötter on the beach with other Jewish child refugees from the “Durres commune” in Albania in 1939.

Courtesy of the Schrötter / Stevens family

Viennese born Susi Shafar (née Rosenfeld) as a young child and later in life at home in Lancashire.

Courtesy of Paul Shafar

The rescue was an act of faith by strangers. Supporters across Britain pledged money and care for children they had never met. The young travellers crossed Europe by train, through unfamiliar landscapes, clutching small cases and identity tags. The few infants included in the programme were cared for by older children during the journey. At ports like Harwich, they stepped off ferries where foster parents and temporary guardians waited on crowded platforms with nervous smiles and hand-written signs. Behind each child’s journey stood a series of difficult decisions. Parents who could no longer protect them at home entrusted them to unknown hands.

Recent historical research has urged a more complex reading of this story.[3] The Kindertransport was a humanitarian triumph, yet also a policy of limits: Britain offered refuge to children, but not to their parents. Each child’s admission required a financial guarantee and responsibility for their care fell largely to volunteers, religious groups and charities. And for many, safety came at the cost of separation, lifelong displacement and ongoing trauma. It’s also important to remember that the scheme was only one thread in a much wider story of child rescue,[4] other children came with their families or in some cases, like four-year-old Liesel Carter, independently and alone.

In Britain, children learned to eat food that was strange to them, to express themselves in a new language, to sleep in unfamiliar beds. Some were welcomed with warmth, patience, an understanding of their homesickness; others found themselves misunderstood, or worse, mistreated.

Laughing, smiling Viennese émigré Elly Korn poses for the camera in this glorious series of wartime photos.

Courtesy of R. Millet & family

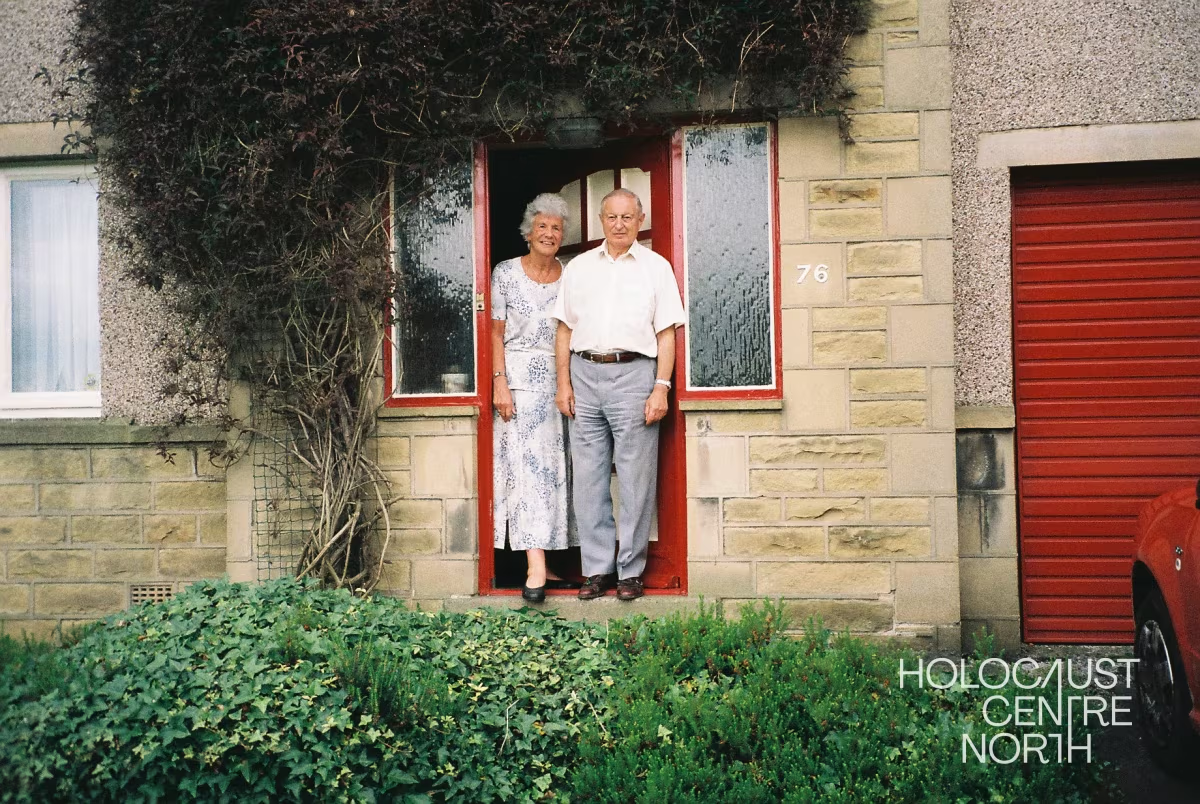

Marianne and Rudi Leavor, who came to England as child refugees in 1937 and 1939 respectively, married in 1955 and settled in Bradford.

Courtesy of the Leavor family

Handmade toy fort won and played with by Tom Kubie as a young child.

Courtesy of the Kubie family

Tom Kubie's homemade diorama; a creative repurposing of an iconic Oxo cube tin.

Courtesy of the Kubie family

Embroidered shirt, one of several children’s outfits the Kubie family brought from Czechoslovakia to England for their young sons.

Courtesy of the Kubie family

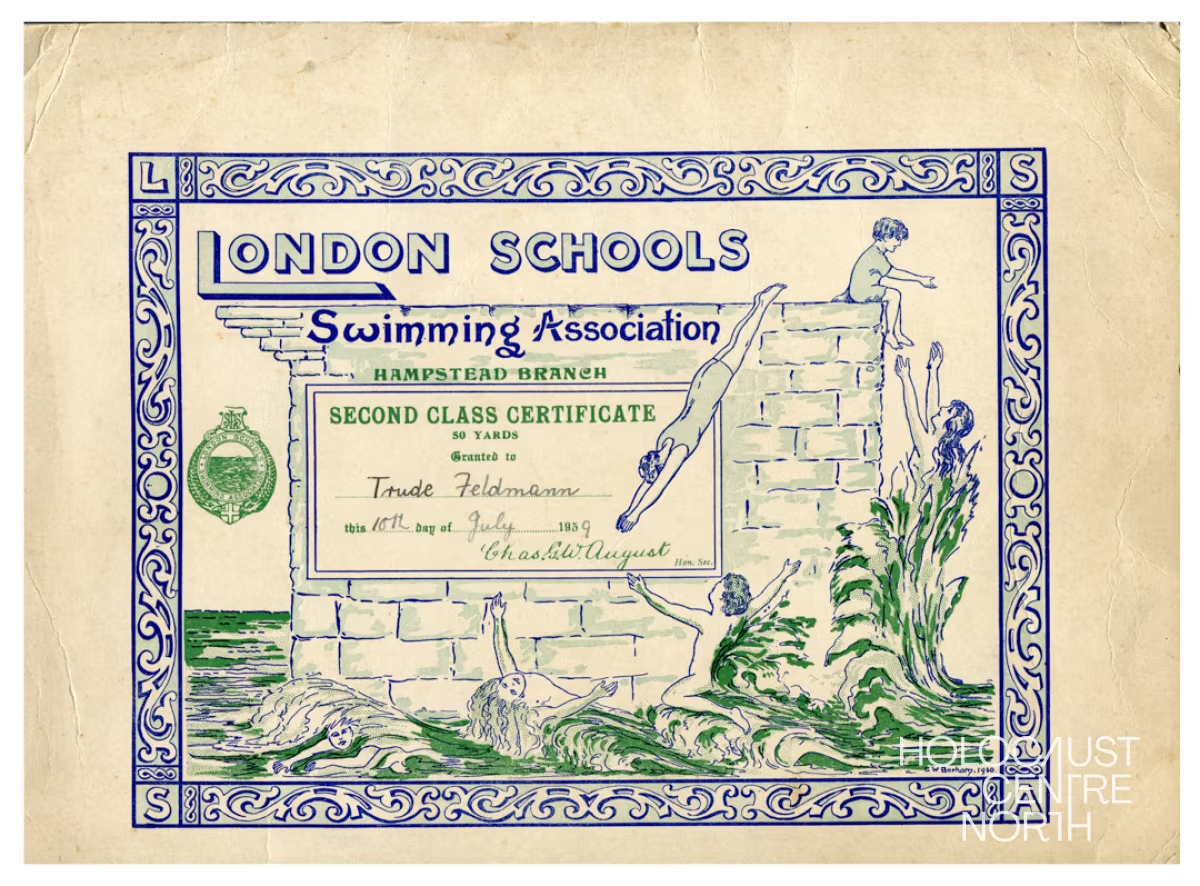

Beautifully illustrated swimming certificate awarded to the ever-accomplished Trude Feldmann shortly after her arrival in England in 1939.

Courtesy of Trude Silman & family

When Britain declared war on Germany on 3rd September 1939, the fragile threads connecting families were cut. Letters, once slow, became near impossible. Unless you had contacts in neutral countries like Switzerland, only short Red Cross messages, limited to 25 words, could still pass through borders.

Yet through all this, these children grew and made new lives. They created homes and families, carrying the memory of those who could not follow. But survival was not an ending; it was the start of a lifelong act of wrestling with questions such as: Who am I now? Where do I belong? What became of those I left behind? Why was I chosen? Indeed, why did I survive?

[1] The New York Times, ‘Evian Parley Closes; 31 Nations Refuse to Take More Refugees’, 15 July 1938, p6

[2] Hansard, House of Commons debate, 21 November 1938, vol 341, cc1460–1463

[3] Hammel, Andrea. The Kindertransport: What Really Happened. Cambridge University Press, 2024

[4] Williams, Amy. German-Jewish Refugees in Britain: The Afterlife of the Kindertransport. Routledge, 2020