Provenance is the story of how objects from the past reach us in the present. It informs their historical value and authenticity. It tells how things move: the routes they take through lives, countries, and institutions; the hands that protect them, the bureaucracies that process them, the circumstances that allow them to remain. It can turn the everyday or ephemeral into the extraordinary. To work with Holocaust-era collections is to work inside those journeys, to follow the winding and uneven paths through which objects survive.

In our Archive, researching and understanding the provenance of Holocaust survivors’ personal belongings is integral, but rarely simple. Some items were brought to the UK with intention: a ring slipped onto a finger before departure, an accordion squeezed among essentials, a favourite framed photo cushioned amongst clothes. Others have more complex histories and were separated from their owners – perhaps seized, misplaced, bartered, hidden or rediscovered years later by strangers who recognised their significance. Each carries the imprint of circumstance: survival, loss, restitution, chance, but you need to know how to read the clues.

Music lover Conrad Leser’s beloved Hohner button accordion, one of the few belongings that he brought to the UK in 1939. He played it for the rest of his life.

Courtesy of Joanna Leser & family

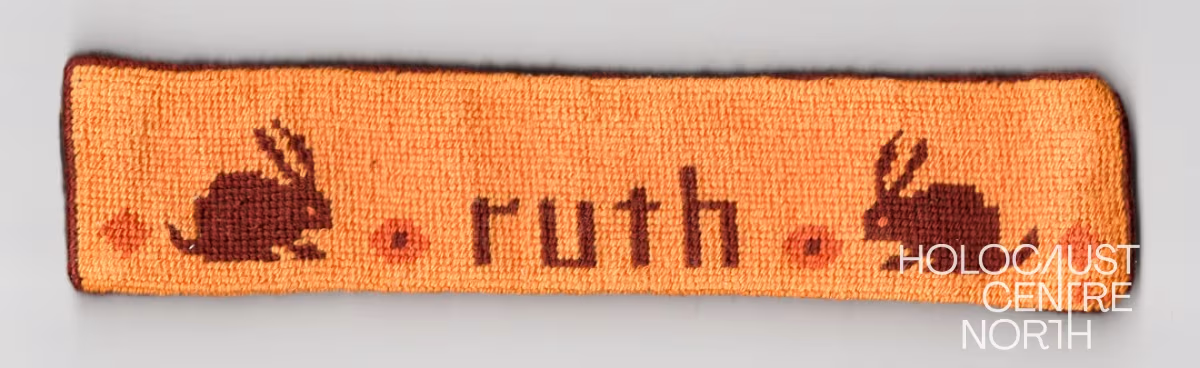

Ruth Sterne’s beloved, hand-embroidered childhood cushion, carefully kept and treasured throughout her life.

Courtesy of Ernest & Ruth Sterne

Some of the incredible array of photos that the Kubies meticulously packed as they emigrated Czechoslovakia in 1939, thereby preserving for posterity a glimpse into the daily life and special occasions celebrated by Jewish families in central Europe before the Holocaust.

Courtesy of the Kubie family

Well-worn, much-loved photo of Hilel Erner, sent to his family in 1940 with a special message: So that my two children do not forget what their papa looks like, I send this picture, in the hope that they will hold it just as dear as if I were with you. A thousand kisses and all good wishes for my wife and the children. Hilel.

Courtesy of the Erner family

Because ongoing relationships with survivors and their families is core to our Archive, we often know an object’s journey intimately. This is a true privilege. Our understanding is deepened through working together: recording testimony, sharing conversations, jogging memories, analysing fragments of handwritten labels, deciphering coded language or nicknames on the backs of photographs. It expands as we trace how an object travelled through time, across borders and languages, through exile and inheritance, until it meets us in the present.

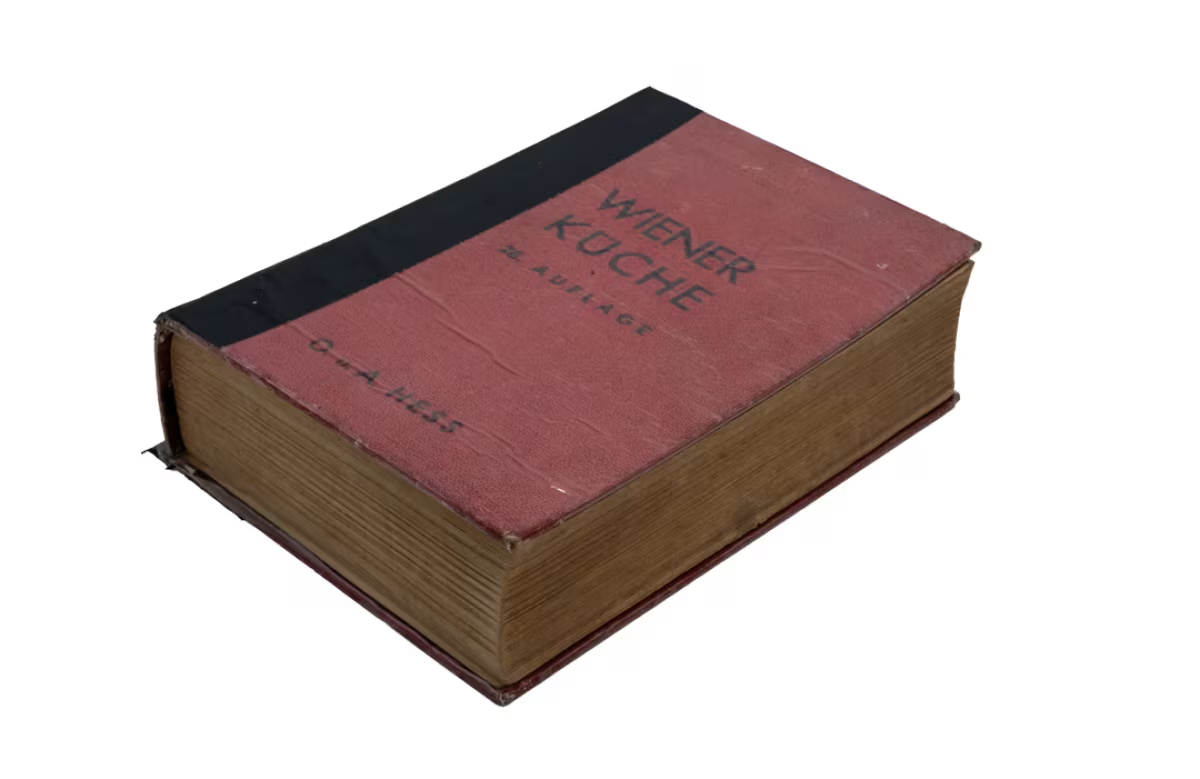

A traditional Viennese cookbook is used again in a northern English kitchen. A wedding ring, once worn in Theresienstadt ghetto-camp, now rests on the hand of a great-grandchild. An accordion, playing German folk tunes in modern Leeds, bridges a family’s two homelands. A single pair of white gloves, given as a symbol of fellowship and love throughout successive generations, before being offered to our Archive. Each example reveals provenance as a form of narrative: the object’s movement becomes part of its meaning and value.

Sofie Fröhlich’s wedding ring, one of a handful of Sofie’s possessions to survive her imprisonment in Theresienstadt ghetto-camp from 1942-1945, and now beloved by her great-grandchild.

Courtesy of Claudia Jonkers

Symbolising purity and equality, these white gloves were given to Niuta Zaslawski by her uncle Maximilian Schatzberger before she escaped Vienna, to use as proof of fellowship at a Masonic lodge.

Courtesy of Lesley Schatzberger & family

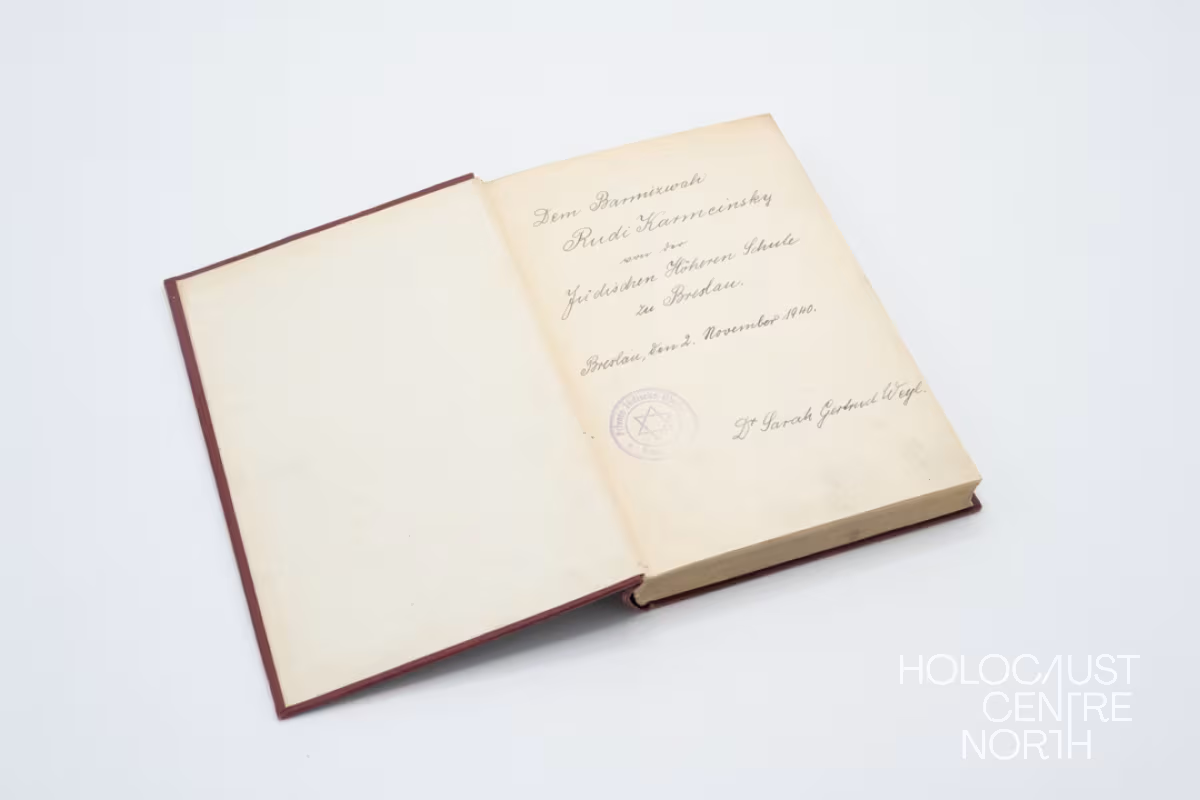

Book of Jewish wisdom gifted to Rudy Karmeinsky by a teacher for his Bar Mitzvah in 1940. Decades later the book was reunited with Rudy’s son after a kind stranger, who bought it in Belgium, tracked down the family using the inscription.

Courtesy of Steve Karmeinsky

Rosl Schatzberger’s 1935 edition of Olga and Adolf Hess’ popular classic ‘Wiener Küche’ (Viennese cuisine),given to Ruth by her mum and during her cookery course in Austria.

Courtesy of the Schatzberger family

What was thought lost can be restored years or decades later, sometimes via a stroke of serendipity, but more often through descendants’ persistent and often painful efforts for formal restitution. A Bar Mitzvah book gifted to a boy in 1940 resurfaces half a century later in a Belgian shop. A kind stranger traces the inscription to the boy’s family in England. In another case, books taken from a man imprisoned in Theresienstadt and later looted for the Austrian National Library, are just recently returned to descendants in Yorkshire. Such moments can be reparative and reconnect stories and lives interrupted by persecution and dispersal. They add another layer to the object’s provenance; a renewed contemporary relevance intertwined with historical worth.

Provenance is also an ethics, a discipline of meticulous attention and continuous research. To trace it is to acknowledge every stage of an object’s life: those who made it, used it, lost it, kept it, found it again. It asks us to hold uncertainty alongside evidence, to accept that gaps and silences are part of the record. In documenting these movements, we record not only possession but care, neglect, resilience, and return.

Vibrant, art-deco, music-themed cocktail shaker and glasses given to Iby and Bert Knill as a wedding present in 1946.

With kind permission of the family of Iby Knill - Chris Knill & Pauline Kinch

Colourful children’s maths game invented by Ruth Sterne as a young teacher in Germany and later sold commercially.

Courtesy of Ernest & Ruth Sterne

Ornate spice box to be filled with fragrant spices and used during the Havdalah ceremony to close Shabbat. It was brought by Marianne Leavor from Germany in 1939.

Courtesy of the Leavor family

Delicate glass bottles from the fashionable French Coty perfume brand, as worn by the ever-chic Nina Kubie.

Courtesy of the Kubie family

Trudi Feldmann’s (later Trude Silman) cherished red scarf, a warming reminder of her mother, Elsa, who Trude never saw again after they said goodbye at Bratislava station in 1939.

Courtesy of Trude Silman & family

Our role continues that journey. When an object enters the Archive, we add our own chapter to its provenance. Digitisation extends that story still further, opening access beyond the archive walls so that new readers and researchers can join the conversation.

Through provenance, these precious objects reveal how memory circulates in material form. Provenance transforms a cookbook, a ring, a pair of gloves, into witnesses of relationships, care and history. It asks us to recognise that the story of survival is also a story of movement, and that every object carries within it a record of the people who kept it, found it, and chose to share it again.